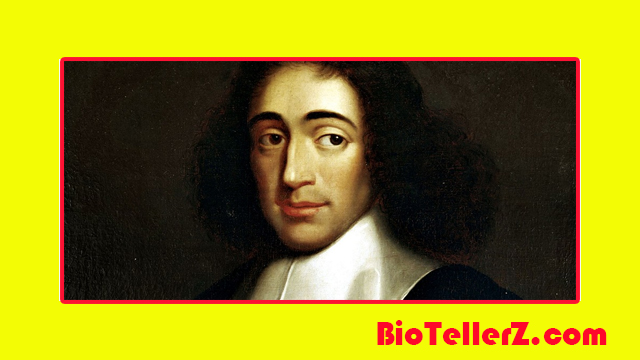

Young Age

In addition to the establishment of the community’s first social and educational institutions, an all-male Talmud-Torah school in 1638. The majority of the teachers were adult males who, before relocating to Amsterdam, had received much of their training at Roman Catholic institutions. They added instruction in various Jewish subjects while passing along to the younger men more or less what they had learned themselves. It is unclear how much traditional Judaism was included in the curriculum. During his time at this school, the young Baruch Spinoza probably studied some Jewish philosophy, including that of Moses Maimonides, and most likely picked up some Hebrew.

When they were 18 or 19, Spinoza’s brother and he established a business selling exotic fruit. Spinoza met other young businessmen from various religious backgrounds at his stall on Amsterdam’s main canal, where he made a number of friends he would keep for the rest of his life.

There is evidence that Spinoza began to draw attention as a potential heretic when he was in his early 20s. Although Spinoza’s case does not have a record of the investigation, all three of them were accused of impropriety after he and two other young men began teaching in Sabbath school. The two other men were tasked with creating doubt in the minds of their students about the Bible’s historical accuracy and whether there might be other accounts of human history that have an equal or even stronger claim to accuracy.

Excommunication

La Peyrère’s heresies may have served as the catalyst for the dispute between Spinoza and the Amsterdam synagogue. During the summer of 1656, he was excommunicated formally. A number of terrible curses were also cast upon him. Herem, which means “excommunication,” or “anathema” in Hebrew, reads like a fierce assault and suggests that Spinoza was deeply despised. In the latter half of the 20th century, it was found that the phrase used in the heresy against Spinoza was one that the Amsterdam Jewish community had borrowed from the Jewish community of Venice.

Despite how severe it was, the excommunication seemed to be carried out somewhat reluctantly. The community allegedly offered to cancel it and even give Spinoza a pension if he agreed to attend High Holiday services and act properly while he was there. Spinoza reportedly objected. At some point after his excommunication, he changed his given name from the Hebrew Baruch to the Latin Benedictus, both of which mean “blessed.”. He was formally expelled from the Jewish community, but he seems to have kept in touch with some of them and even took part in a group discussing Jewish theology in the late 1650s.

Spinoza’s excommunication was controversial, and its causes are still disputed. Naturally, a lot of academics have tried to explain Spinoza’s views by pointing to his religious beliefs. The very tolerant nature of the Jewish community in Amsterdam and the fact that its social and political leaders (the parnassim) were businessmen rather than rabbis, however, have rarely been taken into consideration. In its first century of existence, the Amsterdam Synagogue excommunicated over 280 individuals, but the majority of the cases involved upholding laws and regulations (e. g. , making restitution for debts owed, and keeping commitments made in matrimony), and only a few engaged in heresy. While rabbis could suggest excommunication, only the parnassim had the power to actually carry it out. Given that Michael Spinoza died in 1654, it stands to reason that the parnassim in Spinoza’s case would have been extremely hesitant to excommunicate the son of a recently deceased parnas for ideological reasons.

Engagement College Students

By 1656, Spinoza had made friends with the Collegiants, an Amsterdam-based religious group that disapproved of all governmental doctrine and custom. Some academics claim that Spinoza moved in with the Collegiants after leaving the Jewish community. Some people think it’s more likely that he shared an apartment with political radical and former Jesuit Franciscus van den Enden and taught at the school van den Enden established in Amsterdam.

Related Posts

Donald Trump – Best Guide in 2023